Peter Jackson’s Hobbit films get a lot of flak for being overwrought and overlong. Many of the criticisms are valid enough (I have some of my own), some are a matter of taste, and some, I feel, are simply misguided. My view, as a fan of Tolkien first and Jackson second, is that the naysayers are judging the films for what they’re not. They are not a cinematic translation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s classic novel but an adaptation in the truest sense of the word. And they are specifically an adaptation of events in Middle-earth 60 years prior to Bilbo’s eleventy-first birthday party which include those covered in The Hobbit and the appendices of The Lord of the Rings.

Spoilers follow for The Hobbit films.

To adapt something is to change, alter, or modify it to make it suitable for new conditions, which is where the problems occur for fans of a richly detailed story. No, not merely a story, a whole legendarium (Tolkien himself called it such) that lots of people care a hell of a lot about. The expectation seems to have been that Jackson should have kept to the books closely, should have told the story just as Tolkien did. But ultimately, that’s just not realistic.

It’s not like he didn’t know what’s in the books; in addition to knowing them well, he was surrounded by Tolkien scholars, Elvish linguists, and other literary experts. Rather, he’s an uber-successful director, producer, and screenwriter who has to wrangle massive movie budgets and we’re not. He loves Tolkien’s work but had taken on the self-imposed, if herculean task of maneuvering a beloved tale through the Hollywood machine. Have you ever watched a comic book, novel, or even play adapted to film and thought, “That’s exactly how I would have done it”? If you have, then that’s amazing! If not, well, in this age of Hollywood remakes, reboots, and adaptations, why expect these films to be any different?

I want a faithful adaptation as much as anyone. But I am not a Tolkien purist about it because I think that Peter Jackson adding Tom Bombadil to The Fellowship of the Ring would have been as absurd as, oh, say, adding a scene in The Hobbit where Thorin & Co. enter the Lonely Mountain right after sending Bilbo in—you know, to go in quietly and do what they had specifically employed him to do. “That, Master Burglar, is why you are here,” Thorin says to him. So yes, that scene was too much. Do I love seeing what various chambers in Erebor might look like? The forges, the billows, the vats, the cavernous abyss of a great mine shaft? The fantasy nut in me says hell yes! But the Tolkien reader in me says no, not for a gratuitous and overlong action sequence, and not at the cost of undermining Bilbo’s quiet resolve.

Certainly not at the cost of losing this wonderful moment from the book:

It was at this point that Bilbo stopped. Going on from there was the bravest thing he ever did. The tremendous things that happened afterwards were as nothing compared to it. He fought the real battle in the tunnel alone, before he ever saw the vast danger that lay in wait.

Of course, it’s hard for any film to portray a character’s internal thoughts, which is all that moment is, but I think most of us would agree that Martin Freeman would have done an excellent job visually depicting Bilbo’s trepidation. Peter Jackson opted not to try this, and we can and must live with that. The book is not demeaned, but the movie is the lesser for it.

Likewise, Peter Jackson opted to keep Bombadil out of The Fellowship of the Ring, which it must be remembered was his first foray into Middle-earth. Which, honestly, we’re still lucky even happened. And I agree with nixing Tom not because I wouldn’t like to see him or his oft-referenced yellow boots on the big screen—because that would be both fun and surreal—but because I don’t think anyone but die-hard book fans would have had the patience for him, his lovely but passive wife Goldberry, or his flamboyant, “Ring a dong dillo” self. Simply look at the numerous complaints of “too many endings” levied against The Return of the King. Jackson’s Fellowship would have faltered with the excess of Tom Bombadil (and even the barrow-wights, which I’d dearly love to have seen) and then millions of people would never have come to know or appreciate the greater works of Professor Tolkien. And the Tolkien Estate’s book revenue wouldn’t have increased by 1,000% (in the UK) as they did despite its utter contempt for Jackson’s meddling.

I’m rereading all the books now and I’m enjoying every unabridged word. Likewise, I’m happy to watch Peter Jackson’s six adaptations as a hybrid member of the audience, fully accepting that no one demographic can be fully satisfied. Among the many, you’ve got:

- Hardcore Tolkien fans who gripe at every change from the books (but still go see the films).

- New fans who loved the films and have now discovered the books.

- Action-adventure moviegoers who just want to be entertained but probably won’t ever read but “OMG look how badass that blond elf is with all the arrows and the shield-skating acrobatics and crumbling-tower-climbing and monster-bat-riding!”

- Young girls, according to the director himself, who might be glad to have a relatively strong female character to root for (in Tauriel and Galadriel), where otherwise The Hobbit would have had none.

The point is that untold numbers of people have enjoyed all three Hobbit films, sometimes because of—and sometimes despite—their Jackson-expanded elements. Now that The Battle of the Five Armies has marched into theaters and the trilogy has concluded, I’d like to weigh in on the bigger picture.

First, I found The Battle of the Five Armies to be satisfying and extremely fun. And by that I mean that it’s a fine capstone to the prequels to Jackson’s Rings trilogy. I’ve had no qualms about The Hobbit being split into three films on principle. From the coming of Thorin and Co. to Bilbo’s home (July of the year 2941) to the return of Bilbo to Bag End (June of 2942), about 11 months pass. Meanwhile, from Frodo’s departure with the One Ring from Bag End (September 23, 3018) to all four hobbits returning to the Shire after Sauron’s defeat (November of 3019), about 14 months elapse. The span of diegetic time is comparable. Granted, there are more moving parts and political conflicts during the War of the Ring, but just as in the Rings trilogy, there is plenty happening behind the scenes during the quest for Erebor that Tolkien addressed long after writing it. The White Council moving against Sauron in Dol Guldur is just one part of that.

It’s been said that “the filmmakers have wrung all they could out of the source material,” but I find that to be a lazy stab because it’s simply untrue. Indeed, to me that’s the irony. While three Hobbit films meant there should be room for some fleshing out of otherwise sparse details—the very thing people are complaining about, that he made a short book longer than they felt it needed to be—Jackson still didn’t actually cover everything. I reserve a more final opinion for when the Extended (i.e. the real) Edition of Five Armies comes out, because it promises to include 30 more minutes, but there are elements of the story simply left off.

I can forgive almost any extension or stretching of characters and themes, so long as they’re not completely antithetical to Tolkien’s ideals, but only if the existing story, including the appendices-based backstory, is exhausted first. Beorn’s house; the Eagles and their eyries (and why they help at all); the drunk Wood-elves and the full interrogation of the dwarves; the thrush and its world-saving delivery of vital information; the aftermath of the battle—all of these have been gutted. In the behind-the-scenes features of the DVDs, you can even see that some of it was filmed (such as the captive dwarves being brought before Thrandruil, not merely Thorin), but never made even the Extended cut. Sadly.

But these are movies; they need to take into account a moviegoer’s patience (and bladder). Of course, short making a full-blown movie series (rather than mere trilogy) there is never enough time to cover everything. Think of all that was removed from The Lord of the Rings, which has a full run-time of just over 11 hours. Given that, are you in the “What, no ‘Scouring of the Shire’?” camp or the “Nah, it’s fine as is” camp?

Still, in The Battle of the Five Armies, every second of screen time given to the character of Alfrid was one less we that could have been better used developing the White Council. Explaining who they are exactly, how their Rings of Power relate to one another, that sort of thing. And that’s a real shame. Alfrid is a cartoonish weasel who seems to portray the worst that the world of Men has to offer short of being seduced by Sauron; we already had that in Gríma Wormtongue, but at least he was a necessary, plot-based character. In any case, it seems the Master of Lake-town’s fate in the book has become Alfrid’s fate in the film and the dragon-sickness gets to him. Whatever.

The White Council’s ousting of Sauron from Dol Guldur felt the most truncated. I enjoyed seeing the ringwraiths in their more spectral form, even if their inclusion via the High Fells of Rhudaur were an addition. This is a prime example of where I don’t mind Peter Jackson’s tinkering; it was never made clear by Tolkien where the Nazgûl would have been during this timeframe. No harm, no foul, why not see them again? That said, more spellcasting and less wizard-fu in the Dol Guldur skuffle would have been preferred, but it’s still gratifying to see Galadriel finally invoke some epic, Silmarillion-flavored might. She will one day return there, after all, when the Shadow is defeated. Per Appendix B:

Three times Lórien had been assailed from Dol Guldur, but besides the valour of the elven people of that land, the power that dwelt there was too great for any to overcome, unless Sauron had come there himself. Though grievous harm was done to the fair woods on the borders, the assaults were driven back; and when the Shadow passed, Celeborn came forth and led the host of Lórien over Anduin in many boats. They took Dol Guldur, and Galadriel threw down its walls and laid bare its pits, and the forest was cleansed.

But I do wish her bearing was brighter and less dark-queen creepy, which is clearly meant to match up with her Fellowship manifestation. In Five Armies, she is not being tempted by great power, she’s using her own. I think the visual connection was too much handholding. Likewise, I wish her voice was not once again layered and pitch-dropped—Jackson’s sound crew, having proved themselves throughout all six films, could have done way better than use that cheap trick.

Saruman himself was underused throughout the trilogy, though it’s yet been a joy to see Christopher Lee return to the role. He is the head of the White Council, and though he kicks serious Nazgûl ass in Five Armies, he seemed more horrified than intrigued at the sight of the Enemy, who he was charged to oppose from the start. I was hoping for deeper insight into his own corruption and eventual betrayal. In the canon, he was already desiring the One Ring for himself at this time and had discovered only two years prior that Sauron’s servants were searching the Anduin near Gladden Fields. Which is why he’d finally agreed to move against the Dark Lord, to keep him from finding the One first.

“Leave Sauron to me” seems to be the only hook we get. For now?

As for Tauriel and Kili, this is all there is to it: In An Unexpected Journey and only in the Extended Edition, we see Kili eyeing an Elfmaid in Rivendell, so we know he’s prone to elven interests. Then in Desolation, he meets Tauriel and actually falls for her (as much as a dwarf can in so brief a time) and is saved by her. Then in Five Armies, it all comes to a head and one dies trying to save the other.

I’ll say two things about this subplot then leave it alone, since much has already been said and because it’s a small matter compared to the rest of the story.

Tolkien’s Elves, while portrayed quite differently in the films than in the books (a topic for another time), are still presented as a tragic, if powerful race. To me, the tale of Kili and Tauriel is less about an Elf and dwarf romance as the adversity that lies between an immortal and a mortal. That is a theme that Tolkien cared much more about and he used several times. In Beren and Lúthien, and in Aragorn and Arwen. Even Elrond and his brother Elros were given the choice of mortality or immortality; Elros chose the life, and therefore the doom, of a mortal Man (and surprise, chose a mortal wife), while Elrond chose immortality. They were therefore parted by thousands of years.

There is precedence for a rare fondness between Elves and dwarves despite their ancient racial feud. In The Lord of the Rings, not only do Legolas and Gimli forge an everlasting friendship with far-reaching effects, but Gimli is powerfully and affectionately smitten by the beauty of Galadriel and it changes him deeply. The dude won’t shut up about her sometimes, it’s awesome.

Against these, the cinematic contrivance of Tauriel and Kili’s brief but unexplored love is nothing to fret about. Yes, it’s annoying to see an Elf lose her head, teenager-style, in the midst of a great battle—and more so because she’s one of the few female characters—but she’s still the only Elf pushing to oppose the orcs because it’s the right thing to do. Even Legolas would not have, and daddy Thranduil merely covets gems. The relationship feels a little forced, and the alleged affection between Legolas and Tauriel is also hard to buy into—in part because the films have made Elves colder than their literary counterparts—but it’s also harmless. So a character with little personality in the book (Kili) is given feelings for a character nonexistent in said book (Tauriel). Big deal. It’s not like Jackson gave Bilbo a girlfriend. Thankfully.

Honestly, I’m just happy to see female Elves, period, especially in battle. In the massive ranks of armored and militant Elves—in the Battle of the Five Armies, at Helm’s Deep, or even in the Fellowship prologue—are there any others? I don’t honestly know, but I’ve never noticed any.

The fact is, the biggest portion of the trilogy is the adventures of the titular hobbit, and Martin Freeman’s Bilbo remains the highlight, diminished only in scenes where he’s upstaged by the actions of others. I was quite content with his role in Five Armies, since the “Thief in the Night” sequence was more or less faithful to the book and his involvement in the battle itself was extended only lightly. Bilbo’s parting words with Thorin as the dwarf lies mortally wounded were meaningful to me, if much too abridged—but then that’s generally my only complaint. I do hope for more coverage of the battle’s aftermath in the Extended Edition: Thorin’s funeral, Bard’s coronation, more of Bilbo’s return trip, or any of the things glimpsed in the trailer that didn’t show up in the theatrical version.

If you watch the films and then read the corresponding events in the book, you’ll find that Tolkien’s storytelling method has a curious, tell-don’t-show chronology to it—something he did in The Lord of the Rings but perhaps not as arbitrarily as in The Hobbit. I’ve heard it complained that Fili and Kili’s deaths were “much better” in the book by naysayers of the film. There was no scene at all in the book relating their deaths, merely a past perfect, after-the-fact summation of what happened. All we get is:

Of the twelve companions of Thorin, ten remained. Fili and Kili had fallen defending him with shield and body, for he was their mother’s elder brother.

So I for one am grateful for the things we do get to see brought to life on the big screen. The Rings trilogy was full of satisfying “off screen” moments from the books brought on screen, like the Ents’ assault on Isengard and Boromir defending the hobbits from orcs. Hell, to me Dain Ironfoot’s portrayal in Five Armies was enjoyable even CGI’d as he was, and seeing an army of dwarves gratifies the D&D freak in me. Dain, like Bolg, like Thranduil, like most of the dwarves, are given personalities Tolkien doesn’t take the time to do.

And that’s fine that he didn’t. It was a single book he wrote before conceiving of the enormity of Middle-earth. Tolkien was a revisionist, and even went back and made changes to The Hobbit once he started to write The Lord of the Rings. (In the first edition of The Hobbit, Gollum bets Bilbo his magic ring if the hobbit wins their riddle game—imagine that!) But Tolkien was content merely to bridge The Hobbit with Rings in other ways and not rewrite everything from the start.

2001’s The Fellowship of the Ring is a miraculous, groundbreaking film and each of Jackson’s installments since have, in spirit, style, and Tolkien lore, been like a carbon copy of the previous one, so that 2003’s The Return of the King was still excellent and felt close to Fellowship, but 2014’s The Battle of the Five Armies is certainly a far cry from it. Yes, it’s far more flash and action than rich storytelling and certainly bears even less resemblance to the source material, but it is at least fairly consistent with its own vision of Middle-earth. And that’s what they all are: the vision of one man (Jackson) who stands at the vanguard of an army of talented artists and filmmakers. Because of that army, it’s still a hell of a lot of fun to watch. And Howard Shore’s score still somehow legitimitizes it, just like a John Williams score and a lightsaber sound effect can still, just for a moment, invoke nostalgia in even the crappiest Star Wars film.

The Hobbit trilogy is not perfect, of course not. There are numerous things to pick at. The stone giants sequence in the Misty Mountains was needless showing off of CGI and presented a hazard to the characters not suggested in the book. The barrel-riding scene was turned into an action sequence that downplayed Bilbo’s role in it. But at least the stone giants and the barrels are in the book. Some of the added dialogue just doesn’t work. Fili telling his brother “I’ve got this!” at Ravenhill is gratingly anachronistic and not remotely Tolkien-esque. Though a pretty mild offense, I found Saruman referring to the Necromancer as a “human sorcerer” disappointing because the word “human” is never used in the books to refer to Men. Legolas and Tauriel reaching Gundabad and returning again in so short a time undermines the length of Bilbo’s whole journey. Jackson certainly played fast and loose with geography.

All the birds and beasts have been de-anthropomorphized. The Eagles did not speak, neither does Roäc the raven or the thrush. Beorn’s sheep, dogs, and pony friends don’t serve Thorin and Co. their meal as they do in the book. But these things wouldn’t exactly be in keeping with The Lord of the Rings, anyway—neither Tolkien’s nor Jackson’s.

When I first saw An Unexpected Journey, I loved it but I have learned to accept the things that didn’t play out more like in the book. Why, I fretted, didn’t they use the Great Goblin’s actual lines from the book? Sure, add some new dialogue but don’t replace what was there wholly. But I’ve learned to let it go. As J.R.R.’s own grandson has said, the films “kind of have to exist in their own right.”

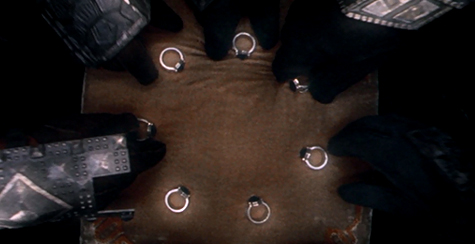

Repeated viewings of all six films continue to impress me, and watching the making-of featurettes on the Extended Editions do shed light on reasons for the changes even if they’re not what you’d have done. For me, I pine not for a perfectly faithful translation of the books but for the additions that could have been. The opportunities for greater context were there, right under Peter Jackson’s nose. We’ve met Radagast (who totally would have been given at least a cameo in Fellowship if Jackson has made the Hobbit films first), we’ve heard of the “two Blueses,” and we’ve seen the White Council in action. Why not use all that to show what Gandalf really is, why he’s constantly prodding everyone to oppose Sauron, and how he had the power to “rekindle hearts in a world that grows chill.” Why not address the Nine, the Seven, and the Three? Especially the Seven, since the fate of Durin’s folk, their greed for gold, and Sauron are all related?

But alas, that would not have been done so easily, as a lot of that lore comes from The Silmarillion and the Tolkien Estate has not yielded that license. Not to mention the awesomeness of The Unfinished Tales, which reveals all kinds of good stuff about the Istari.

So again, the films are not the books and shouldn’t be judged as such. If they’re not what you hoped for, fair enough. You can’t please everyone, but don’t try and take them away from those they did please. As old John Ronald Reuel himself wrote in his Foreword to the Second Edition of The Lord of the Rings:

As a guide I had only my own feelings for what is appealing or moving, and for many the guide was inevitably often as fault. Some who have read the book, or at any rate have reviewed it, have found it boring, absurd, or contemptible; and I have no cause to complain, since I have similar opinions of their works, or of the kinds of writing that they evidently prefer.

Personally, I’m pleased with any franchise which shows, however briefly, Belladonna Took’s son as a small child, merrily play-battling with Gandalf the Grey, a symbolic and touching moment for all that would follow—not only to show that a mighty Maia spirit was fond of the simple Shire folk but also why he would select one of them particular to turn the tide.

Jeff LaSala can’t wait to read The Hobbit to his son, who is much too young to realize how nerdy his dad is. For now, both will just have to play with plush hobbits and Istari.